Servus Litterae

Sometimes, in the fight to save the light, we end up extinguishing it with our own ardor.

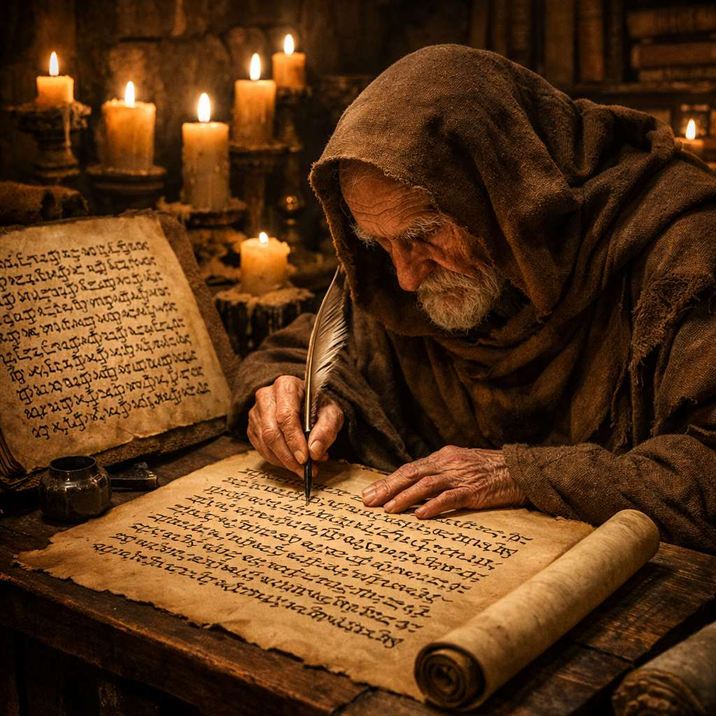

One day I stepped into the small, forgotten library of the sand city. Its broken columns rose from the dunes like fingers of stone, reaching toward a sky that no longer dared to set. I descended a dusty staircase and entered a room where candles still burned, though there was no window, no door through which air could have entered. And there, in a corner, I saw an old monk bent over a manuscript, quill in hand, copying something with a devotion that gripped my heart.

His hands were shaking, and his eyes, half-blinded by decades of dim light, could barely make out the letters he was transferring from one parchment to another. As I got closer, I saw that the original manuscript was written in a language no one had spoken for centuries. And the copy the old man was making was graphically perfect, but meaningless to any living mind. It was a Transcriptio Vacua a transcription of the void, a meticulous preservation of forms that no longer contained anything. Sometimes, fidelity to the letter becomes betrayal of the spirit.

Leadership: Can you recognize a time when your devotion to an art form exceeded that form's ability to carry meaning?

Why do you continue this laborious work? I asked the old man, as if I had disturbed a liturgy of silence. He did not look up from the page, but answered me with such solemn silence: Because if I stop, the light will go out. It was the voice of a man who had repeated the same words so many times that they had become a prayer, a kind of sacred mantra: Every letter I copy is a torch held alight in the darkness.

And then I looked around the candles flickered, the shadows arched on the walls, and the old man's eyes, red and inflamed, could hardly see anything of what he was transcribing. The paradox was painfully obvious: trying to preserve the light of knowledge, he was sinking deeper and deeper into physical and mental darkness.

In Umberto Ecos novel The Name of the Rose , the monasterys hidden library contained texts deemed too dangerous to read but at least they had meaning, they had power, they could transform minds. Here, in the ruins of this forgotten library, there was no longer any danger, because there was no longer any meaning. The old copyist had become a slave to the letter, a prisoner of signs that no longer communicated anything, but simply existed. He did not preserve knowledge, but only its decorated coffin. Or, perhaps, a truth from The Name of the Rosesuited him better :

"The reasoning that our mind constructs is like a net or a ladder, which is built to reach something. But afterwards, the ladder must be thrown away, because it is discovered that, although it served, it was meaningless."

Leadership: Do you feel that attachment to an art form can blur the visual perception of the deeper meaning that underpins the act of creation?

I sat by his side until dawn, watching his pen trace with precision signs that neither I nor anyone else in this world could decipher, but only he. And I wondered if this was not the ultimate temptation of any keeper of wisdom to confuse the container with the contents, the map with the territory, the letter with the spirit. I suppose, however, something else: the old man believed that the salvation of the world depended on the preservation of each letter. But the world does not need letters it needs meaning. And meaning is not preserved by copying, but by understanding, by reinterpretation, by bringing back to life what otherwise remains a mummy. Memory does not guarantee truth.

When I asked him if he had ever understood what he was writing, the old man paused for the first time in all the time he had been there. Clarity is lost in the haze of old age. He looked up at me, and I saw a glimmer of pain in his eyesthe pain of one who knows, deep down, that his whole life has been a futile effort. No, he whispered, pain in his voice, after I had watched him for a few moments in silence. But I hoped that someone, someday, would come along and understand. I realized then that he was not just a copyisthe was a guardian of hope, bound by a silent oath, lost in the illusion that meaning would return. His tragedy was not his useless labor, but that he had already become a letter in a forgotten alphabet.

Leadership: Are you ready to give up form to save essence, even if that means betraying the letter to stay true to the spirit?

I left the library before the sun rose, leaving the old man to continue his transcription. That, too, is a work of art: to transform illusion into mission, so that life becomes meaningful. So I didnt stop him, I didnt judge him. Who was I to tell him that his lifes work was in vain? Perhaps the act itselfthe devotion, the perseverance, the refusal to give inhad a value that I couldnt see. Or perhaps I was lying to myself, preferring compassion to truth. Then I climbed the dusty stairs and stepped out into the cool morning air, with a question that has haunted me ever since: when exactly does sacrifice become captivity and when does loyalty turn into slavery?

And so I wrote, in my sand book, the following note, which I could not tear myself away from even for a moment:

"I learned from an old monk that there is no more dangerous devotion than that to forms that have lost their soul. The letter without a spirit is a beautifully decorated tomb. And he who spends his days guarding tombs forgets that his mission is to guard life, not its death. The salvation of the world comes not from the preservation of signs, but from the revival of the meaning that once gave birth to them. Nearing the end, man no longer asks himself what he has lived, but whether his life had a meaning that escaped him even as he was writing it."

Leadership is manifested through the ability to distinguish between living fidelity, which adapts form to preserve essence, and dead fidelity, which sacrifices essence to preserve form.

Servus Litterae is the symbol of that copyist who taught me that blind devotion can become the most refined form of betrayal. In the dusty silence of that library, I understood that it is not the letters that must be saved, but the mind that wrote them in light. And when the light has gone out, the one who continues to copy is no longer a keeper of knowledge, but a prisoner of his own faith a slave to the letter that has long forgotten that it was once free. And, once again, something vibrates prophetically from the novel The Name of the Rose :

"The more I read this story to myself, the less I succeed in understanding whether there is any plot in it that goes beyond the natural unfolding of events and times that enclose it. And it is a difficult thing for this old monk, on the verge of death, not to know whether the letter he has written contains some hidden meaning, or whether it has more than one, and many, or none at all. But this inability of mine to see properly is perhaps the effect of the shadow that the great approaching darkness casts over the graying world. Sometimes, he who has lived the longest is precisely he who has understood the least the meaning of the traces left by his own life."